Explore Ezra Pound’s influence on the Modernist Literary Movement by clicking on and activating the Story Map above.

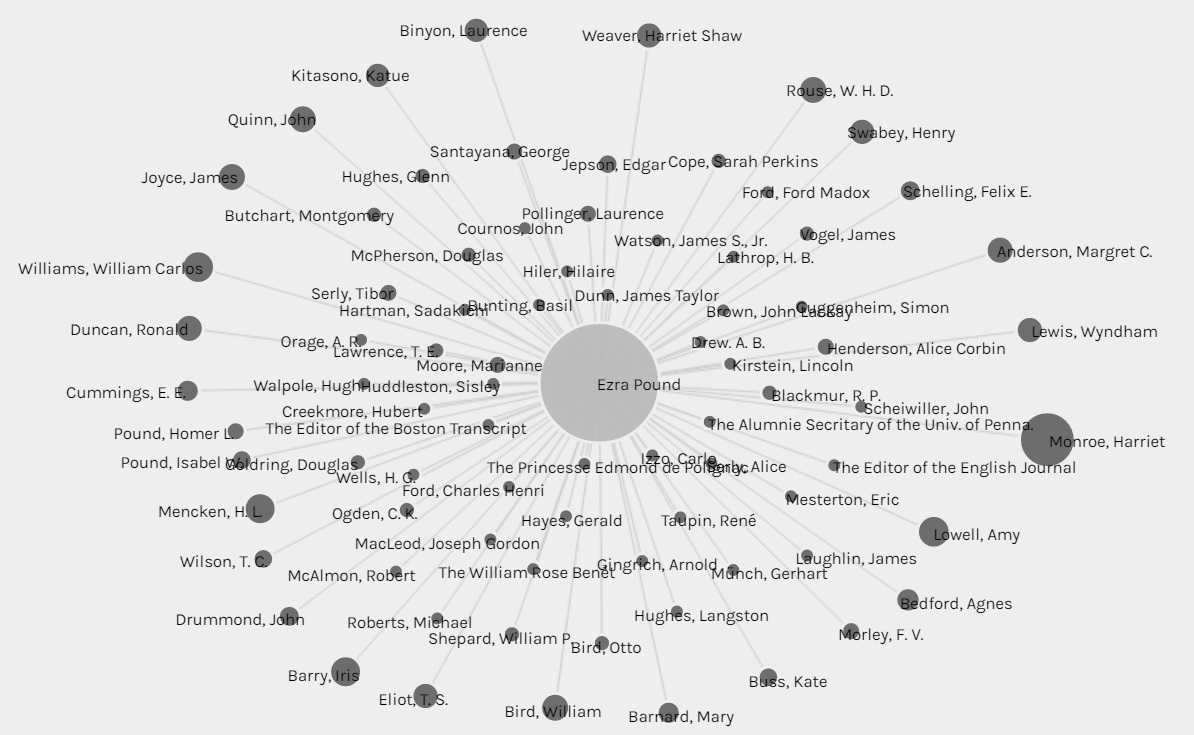

Besides looking at Ezra Pound’s influence, our team also decided to analyze Ezra Pound’s correspondence network, using a digitized copy of The Letters of Ezra Pound made available by archive.org to better understand who Pound was exchanging ideas with. In this way, we were able to get a better sense of just how influential Pound was in the literary circles of his time. We found that his correspondents included Wyndham Lewis, the founder and editor of Blast, Margaret C. Anderson, editor of The Little Review, and Harriet Monroe, editor of Poetry. He also frequently connected renowned poets and authors, such as James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, E.E. Cummings, and William Carlos Williams.

This network analysis illustrates some of the connections upon which the most influential of the little magazines were founded. These small-scale connections, between artist, friend, and editor, set the stage for the larger connections between artist, reader, and editor that would make the little magazines influential in literary and social movements. Here, at the heart of the connections between now-immortalized writers and the editors who first published them, sits Ezra Pound. While Pound was by no means the most published or most celebrated writer to appear in any of the magazines (and his credits as editor are limited to the first Imagist Anthology), the vast web of correspondence reveals the influence he held with multiple publications and celebrated writers. He was instrumental in connecting writers to magazines, and in sending work he believed to be worth reading to editors. One of the shortcomings of this data is that while the network shows who he wrote, it does not reveal anything about the content of the letters. From England, he sent manuscripts by the likes of Joyce, Eliot, and Williams to Poetry and The Little Review, among others, providing the magazines with some of their most controversial and enduring content.

Pound’s role as a connector, as illustrated by the network, helped to elevate voices that were otherwise rejected or hidden. Writers like Joyce, whose novel Ulysses was found to be in violation of the United States’ obscenity laws and was not compatible with the work being published by mainstream publishing conglomerates, were able to have their work disseminated by these independent magazines. In turn, the magazines then became the carriers of some of American literature’s most dominant voices of the 20th century.

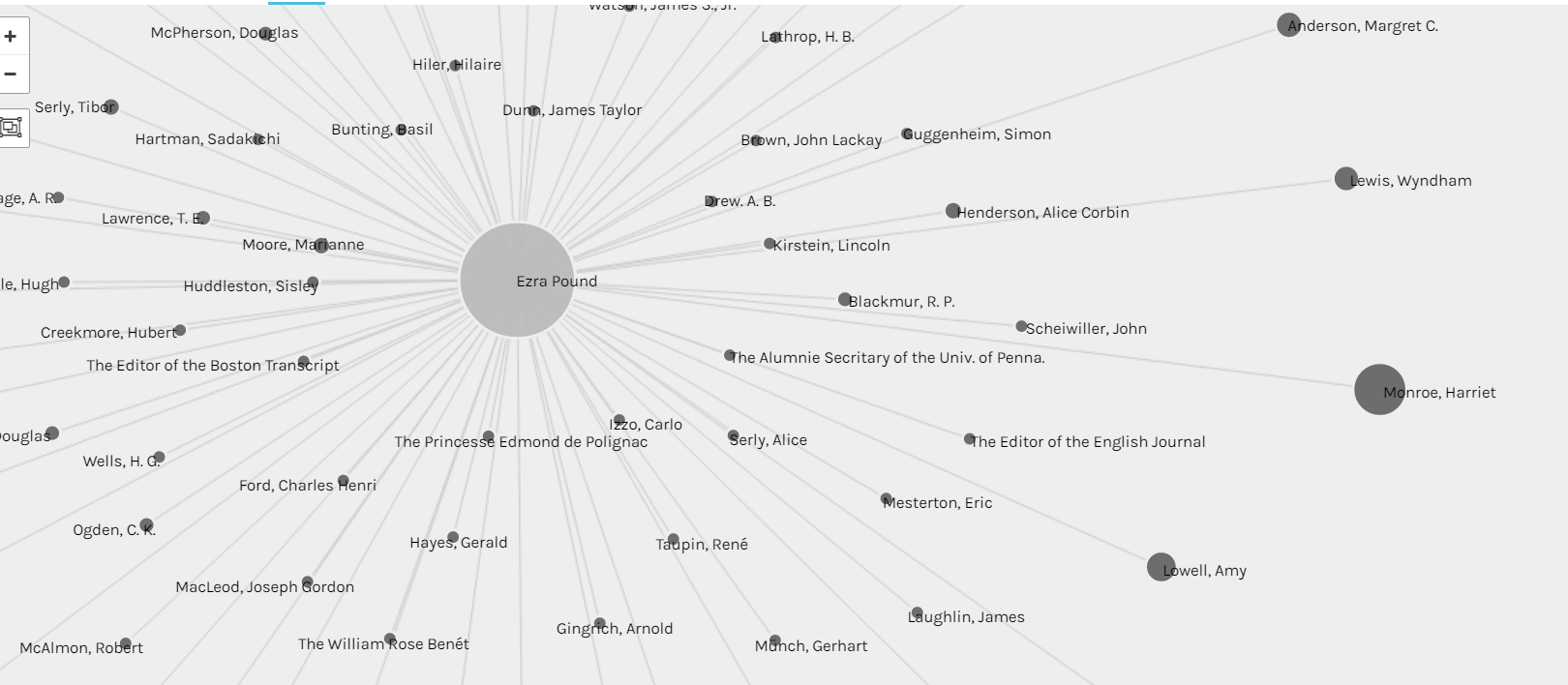

Close up of Pound’s correspondence with Harriet Monroe, editor of Poetry.

One correspondence particularly worth noting and of interest to our team was that between Pound and Harriet Monroe, the longstanding editor of Poetry. Pound exchanged more letters with Monroe than anyone else, as shown by the size of her nodes with respect to all the rest. While we cannot say that volume of letters exchanged corresponds with the amount of influence Pound held at the publication, it can be said that Pound spent much time discussing writers with Monroe which he thought had potential, debating editorial decisions he supported or disagreed with, and opinions on work she was considering.

Pound’s network of correspondence, above all, illustrates how one person, through their involvement with little magazines, could work to elevate a multitude of voices and push forward artistic movements that otherwise may have remained stagnant. Without Pound, writers such as T.S. Eliot and James Joyce could very well have gone unpublished and unheard. The connections shown by this network, the connections upon which the little magazines were built and which they then fostered, were what enabled these magazines to raise quieted voices and push forward both literary and social movements.