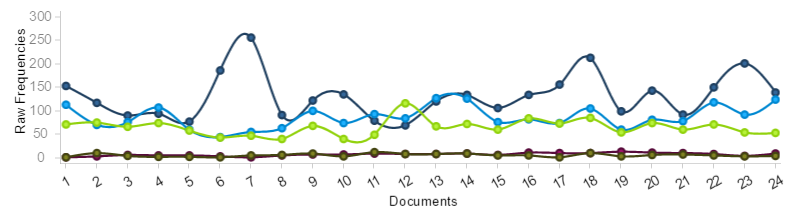

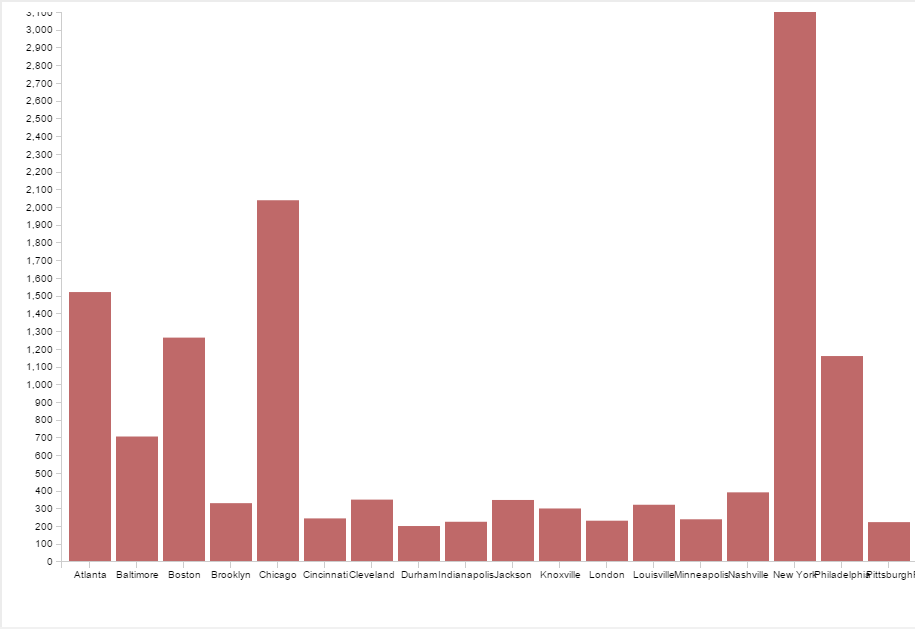

We examined the extent to which magazines with explicit associations to political movements, such as The Crisis which was funded by the NAACP, were concerned with regional or far-reaching issues. The Crisis was a slender magazine edited by W.E.B. DuBois promoting the Civil Rights Movement at a seminal period of its history. It served as a vocal platform for African Americans to discuss their place in the United States. To determine the extent to which The Crisis dealt with regional stories or issues as opposed to national ones, we used Voyant and tracked how frequently different cities were mentioned. The graph above shows the top twenty cities mentioned throughout the entirety of The Crisis, which ran 1910-1922 and published a total of 146 issues. New York was the city most often mentioned, showing up over 3000 times-unsurprising for a journal published in New York City. Chicago was the second most frequently named city, with 2041 mentions and Atlanta was third with 1523. Notably, however, other cities received far fewer mentions. Philadelphia, which is #5 in terms of mentions, is named 1162 times, #6 Baltimore, named 708 times, and then #7 Nashville with a mere 393.

The concentration of place-names on urban centers worldview suggest that the magazine was mostly focused on big-city issues and concerns. Rural civil rights, it would seem, would have to wait. Equally suggestive are the two most mentioned cities; New York and Chicago, cities that, while undoubtedly facing racial issues just as the rest of the country was, were in the Northeast and Midwest and not in the south, where the majority of the civil rights movement as it is commonly thought of today took place.

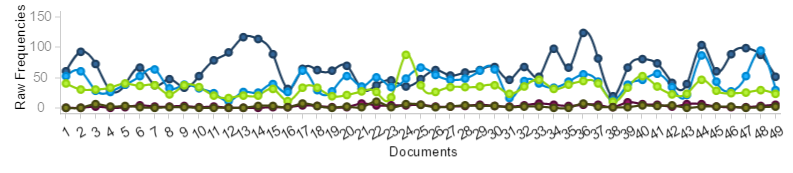

Because of this insight, we decided to also track the frequency of a couple different cities throughout the corpus. We tracked New York, Chicago, Atlanta, as well as Greensboro (#24 in mentions) and Birmingham (#27), two southern cities that would later become crucial to the civil rights movement. We found that while the top three fluctuated in mentions, Greensboro and Birmingham stayed consistent, never topping more than a few mentions per issue. Partially, this might be attributed to the spread of the movement; cities like Atlanta in the south, and the robust industrial hearts of Chicago and New York, were relatively liberal cities, affording free spaces for these movements to gain steam.

From this we can see that The Crisis, while it did cover issues spanning a wide geographical range, focused heavily on those taking place in New York, the city of the magazine’s publication, and Chicago, and did not mention as often southern cities, something which seems at odds with our 21st century understanding of the civil rights movement.

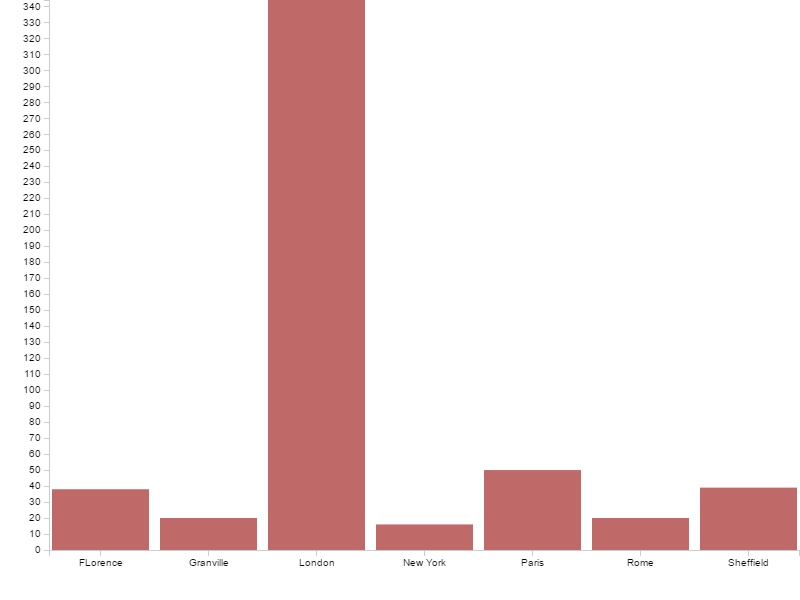

Our work with the Freewoman is a far smaller corpus, and so fewer conclusions can be gleaned. The Freewoman, an ultimately British-based journal, seems to overwhelmingly focus on the geography of the Isles, featuring a remarkably high number of references to London and Sheffield in particular. Together they outnumber mentions of any other world cities combined. New York, itself a Modernist journal hub, only appears 16 times in the text. Other European cities are discussed more often, with some countries, like Russia (not in chart), were mentioned about 20 times. But by and large, the Freewoman seemed to stand as a national work for British affairs, mobilizing the communities at home without drawing heavily on connections over the Channel or across the Pond.

Part of this may seem surprising, though it is vital to keep in mind that the writers of the Freewoman (and the subsequent, but similarly short-lived New Freewoman) were writing from the fringe of the fringe of radical ideas. Women’s suffrage, and frank conversations about sexuality, feminism, and marriage found less traction and ecumenism than did even, say, the avant-garde poetry of Pound or Eliot. These factors might also well explain why the Freewoman never developed the connections or breadth to develop an international readership or authorship. A local base would have to be established, presumably, before works farther afield could be gleaned.

It would seem in both movements, we are watching seminal movements -foundational spaces for far larger movements to snowball long after the presses had grown cold. The Civil Rights and Women’s Suffrage movements familiar to a contemporary audience were still infants in the turn of the previous century.